The results of opinion surveys don't usually shock me. But I confess to being stunned by what Cato Institute researchers were told when they included this question in a recent poll of 2,000 American adults: "Would you favor or oppose the government installing surveillance cameras in every household to reduce domestic violence, abuse, and other illegal activity?"

Government cameras spying on you in your own home? That has to be a no-brainer, right? Surely, I would have thought, nobody wants the feds looking over their shoulder at every moment of every day.

I would have been wrong.

It makes me feel slightly queasy to type these words, but 14 percent of the survey respondents — nearly 1 in 6 — told Cato they would favor such government surveillance. Another 10 percent said they had no opinion either way. In other words, one-fourth of those surveyed wouldn't object to the government watching and recording everything they say and do.

But that's not the worst of it. Support for 24/7 surveillance was especially high among those younger than 30. An astonishing 3 out of 10 respondents born after 1993 said they would welcome round-the-clock monitoring by the government. By contrast, respondents in their 40s, 50s, and 60s were almost wholly opposed.

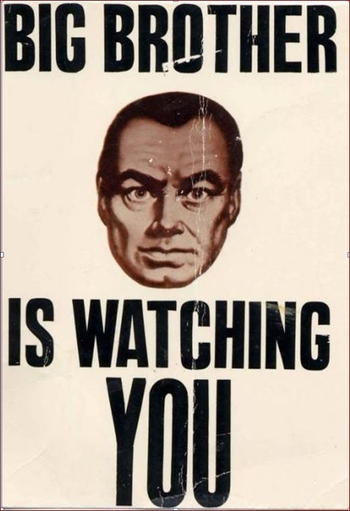

In George Orwell's great novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, a nightmarish masterpiece of life under totalitarianism, every citizen is constantly under the watch of the government. Wherever they are — at home, at work, on public streets, in shops, even in bathrooms — two-way electronic devices keep people under the scrutiny of agents known as the Thought Police.

"The instrument (the telescreen, it was called) could be dimmed, but there was no way of shutting it off completely," Orwell wrote.

How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time. But at any rate they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to. You had to live . . . in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.

First published in 1949, Nineteen Eighty-Four was Orwell's warning of what unchecked state power could turn into — a warning informed by the horrors of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, with their cults of personality, unremitting deceit, repression of dissent and independent thought, and use of technology to destroy privacy. The sinister telescreen reinforced the right of the state — symbolized by Big Brother — to see and hear everything. Private conversations, words written in a diary, a rendezvous with a lover: The government could keep tabs on all of it. Winston Smith, the protagonist of Orwell's novel, is no hero. He is a weak and wistful man who resents the regime — and is ultimately broken for it. The book's final words are among the most devastating in all of literature: "He loved Big Brother."

All these years later, with everything we have learned about the evils of unrestrained government, is it really possible that almost a third of Generation Z is prepared to love Big Brother?

"We don't know how much of this preference for security over privacy or freedom is something unique to this generation (a cohort effect) or simply the result of youth (age effect)," writes Emily Ekins, the Cato Institute's director of polling. She hypothesizes that Americans who grew up during the Cold War with an awareness of the elaborate Soviet apparatus of repression learned early on to recognize the "dangers of giving the government too much power to monitor people." Members of Generation Z, on the other hand, came of age after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, so they never internalized the evils of an all-seeing state.

Color me skeptical. Totalitarian tyranny didn't vanish with the end of the Cold War. Monstrous governments in the 21st century are no less oppressive than the Soviet Union was in the 20th. Think of the cruelties inflicted by today's regimes in China, Iran, or North Korea. The thought of being watched at all times by government cameras should be as unnerving to Americans under 30 as it is to their parents and grandparents.

A better explanation, perhaps, is that Generation Z has been indoctrinated to regard safety, not freedom, as the highest good — so much so that many would rather be under the nonstop watch of the state than face the possibility of being abused or endangered.

If so, they are in for a fearful awakening. What little protection they might gain from being under the authorities' constant watch is as nothing compared with the peril they would face. Benjamin Franklin's famous admonition is as relevant as ever: "Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety." Inviting Big Brother into your home will not keep Gen Z-ers safe. And by the time they realize what they have given up, it will be too late to get it back.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Why we fly the flag

In the spring of 1963, the civil rights activist Medgar Evers — then deeply involved in organizing pro-freedom student boycotts in Jackson, Miss. — had a brainstorm. For months, young Black protesters had picketed downtown, brandishing signs that conveyed their message of justice and decency: "I am a man." "Freedom Now." "End Brutality in Jackson." But a city ordinance made picketing illegal, and the students' signs were routinely confiscated by Jackson's police or smashed by hostile mobs.

"As Flag Day approached, Evers considered this problem," wrote Woden Teachout in "Capture the Flag," a history of American patriotism. "What if the protesters carried American flags instead of signs? Evers had little faith in the enlightenment of the Jackson police force, but he doubted that the police would seize the flags. There was certainly no law against carrying an American flag."

It was a shrewd insight that helped turn the tide of the civil rights movement.

With Flag Day only two weeks away, Jackson demonstrators started to incorporate flags into every event. [On June 1], a hundred marchers carrying American flags were . . . arrested and thrown into garbage trucks. Two days later, the chief of police confiscated flags from six downtown picketers. A day after that, nine students carrying flags and wearing NAACP T-shirts were arrested. All of a sudden, flags were the hallmark of Jackson protests.

Since 1954, activists had spilled many words on the Declaration, the Constitution, and the nation's history, showing that integration was the most truly American legacy. The flag made these themes explicit and visceral. American nationhood, it argued, was not the story of a white nation: Instead, it was the story of equality and democracy.

As Americans across the country saw images of segregationists in the South attacking peaceful marchers with fire hoses, dogs, and clubs, their revulsion was magnified by the fact that so many of the marchers were carrying flags. Evers was assassinated on June 12, 1963 — two days before Flag Day — but his spirit lived on in the Stars and Stripes that became a key element of the movement for which he gave his life.

It was on June 14, 1777, that the Second Continental Congress passed a resolution providing "that the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation." Though Flag Day is not a federal holiday, the flag itself has become the most revered sacramental object in America's civil religion.

"Protestors carry the flag to associate their causes with the nation, wave the flag to attract attention, or burn the flag to express contempt," writes Peter Gardella, a scholar of religion at Manhattanville College. It is impossible to overstate the emotional and symbolic power of the flag, or the willingness of Americans to risk their lives in its defense.

The Medal of Honor, the nation's highest military decoration — has been awarded numerous times to soldiers who displayed uncommon heroism to save or rescue an American flag. One of them was William Harvey Carney, who escaped from slavery in Virginia and enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. During the unit's legendary assault on Fort Wagner, S.C., (depicted in the 1989 film Glory), Carney retrieved the regiment's flag from its fatally wounded bearer and carried it to the Confederate parapet through a hail of bullets. When the Union regiment was forced to retreat, Carney made his way back across the battlefield while being wounded two more times. Incredibly, he managed to return the flag to the Union lines, telling his fellow soldiers: "Boys, I only did my duty; the old flag never touched the ground."

Reverence for the flag can be taken too far. During World War I, Congress and many states passed laws making it a crime to utter "disloyal language intended to cause contempt for . . . the flag." During the Second World War, some states made saluting the flag in schools compulsory, and students who declined to do so for religious reasons could be expelled. In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed a federal law criminalizing flag desecration. It took five rulings by the Supreme Court — in 1969, 1972, 1974, 1989, and 1990 — to finally establish the principle that the freedoms symbolized by the flag include the right to burn or deface that flag.

At its best, however, reverence for the flag can be a mighty unifier. Following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Americans by the millions turned to the Stars and Stripes to express the powerful emotions they felt. In the space of 48 hours, Wal-Mart sold 450,000 American flags. The flag manufacturer Annin & Company received so many orders for flags that its production was backed up until the following summer. Flags were raised on innumerable street corners, waved from cars and trucks, worn on millions of lapels.

In some quarters, the post-9/11 surge of patriotic feeling triggered revulsion. Columnist Katha Pollitt exhorted readers in The Nation to "Put Out No Flags." When her daughter wanted to fly a flag from the living room window in honor of the victims and in solidarity with other Americans, Pollitt refused on the grounds that "the flag stands for jingoism and vengeance and war." At the National Press Club a few years later, CBS news anchor Katie Couric lamented the widespread displays of public patriotism, disparaging "the whole culture of wearing flags on our lapel and saying 'we' when referring to the United States."

When I was a child in South Euclid, Ohio, the Jacoby home was one of many in the neighborhood that flew the flag on the Fourth of July, Memorial Day, Washington's Birthday, and other national holidays. I never asked my father, an immigrant from Czechoslovakia who had survived Nazi and Communist tyranny, why we did so. I never had to.

Like countless other immigrants to the United States, like Medgar Evers and the civil rights marchers in 1963, like William Harvey Carney at Fort Wagner, my father intuited the real significance of the American flag, even if he couldn't have put it into words.

In its 247 years of independence, the United States has often fallen grievously short of its values and ideals. But it is those values and ideals that the flag embodies, not the failure to live up to them. To put out the flag is not to proclaim that America can do no wrong. It is to believe in its great capacity to do right — to reaffirm the truth that America has been a powerful force for good in the world, and that it remains, in Lincoln's words, the last best hope of earth.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Faulkner: Be not afraid

I confess that I've never read any of William Faulkner's books, though I have most of them on my shelves and hope to get to them one day. I have, however, finally read something of Faulkner's, and I urge you to read it too: his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, delivered in Stockholm on December 10, 1950.

Its theme is resistance to the mood of fear and world-is-ending alarmism that was as prevalent in some elite circles 70 years ago as it is today. The panic then wasn't focused on climate change or overpopulation or gun ownership or COVID-19. It was focused on the Bomb. In the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the best and the brightest were sure that mankind was racing toward nuclear self-annihilation. That was the era of the arms race with the Soviet Union, the "duck and cover" classroom drills, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and its "doomsday clock," the dread of a mushroom cloud.

Faulkner rejected the hysteria. He insisted that writers must reject it too.

"Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it," he told his audience.

There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

It is those timeless challenges, the ones as old as human nature itself, to which the serious writer must be attuned, Faulkner said — not the ephemeral dystopian hobgoblins that dominate modern discourse. A true writer, he insisted,

must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed – love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse.

At a time when Americans were being told they would likely die in an atomic holocaust, Faulkner asserted: "I decline to accept the end of man. . . . I believe that man will not merely endure: He will prevail."

The whole speech is very short — under 600 words. You can read it at the Nobel Prize website. It will still be a while before I get a chance to dig into "The Sound and the Fury." But now that I have belatedly had my first taste of Faulkner's work, my appetite is whetted for more.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"We dribbled our drinks onto the checkered-tile floor. And for that moment, at least, I felt like the luckiest man alive." — Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father (1995)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.