RIGHT AFTER his inauguration on January 20, 1993, President Clinton signed his first executive order. It barred senior administration officials, for the first five years after leaving government, from lobbying any agency with which they had been involved. This first official act of the Clinton era (which also banned top appointees from ever lobbying on behalf of a foreign government) established, a White House press release proclaimed, "the most stringent ethical requirements of any administration ever."

Eight years later, 23 days before leaving the White House, Clinton signed a new executive order revoking the first one.

At one level, this was merely another cynical act by a supremely cynical politician. But it was also a kind of declaration that for Clinton and his coterie, the first priority of the post-White House years would be to make as much money as possible.

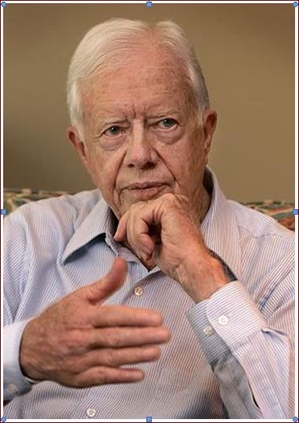

Last week I wrote that Clinton should break with the money-grubbing precedent set by Gerald Ford and George Bush the Elder. Instead of becoming a celebrity-for-rent, willing to appear just about anywhere and with just about anyone if the fee is big enough, I suggested that he emulate Jimmy Carter, who has refused for 20 years to cash in on his status as a former president.

"I think it's inappropriate for an ex-President to be involved in the commercial world," Carter said at a press conference after his defeat in November 1980. "There may be some kinds of benevolent or nonprofit corporations in which I will let my influence and my ability be used, but not in a profit-making way."

He has been as good as his word.

The only board of directors Carter has agreed to join is that of Habitat for Humanity — an organization that is now world-famous because of the extraordinary efforts of its most famous volunteer. Since 1984, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter have personally helped build hundreds of homes for the poor, putting up studs and laying brick at building sites from New York to Peru. The Carters' example has inspired thousands of other volunteers and generated glowing coverage by the press. And as if that isn't enough, Carter has also used his contacts and access to raise millions of dollars for Habitat. Not since Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia — and then designed its buildings, supervised their construction, drew up a course of study, and selected the faculty — has an ex-president done more to nurture a charitable endeavor.

Some of Clinton's defenders excuse his rush to make money by noting that his legal bills are very large. They are, but that is no reason to profiteer off the presidency. Carter, too, left office in debt. His peanut warehouse, a lucrative concern when he became president but in a blind trust since then, was $1 million in the red. The news came as a shock; Carter wasn't told until shortly before his term in office expired. To his sorrow, he was forced to liquidate the business, which he had inherited from his father. He could have opted to grab the easy money numerous corporations were dangling before him. He never considered it.

Eschewing the lecture-circuit-and-corporate-board hustle would not condemn Clinton to a life of penury. His government pensions will pay more than $180,000 a year, on top of the $200,000 or so he will get for staff, office, and travel expenses. His memoirs will earn him millions. His wife is getting $8 million for a book of her own. The Clintons are now a very wealthy couple. They will still be wealthy even after their lawyers are paid.

Clinton returns to private life badly tarnished. Most Americans have a low opinion of his character. The scent of scandal and impeachment hangs over him. If he really wants to rehabilitate his reputation — and what could he want more? — he should follow in Carter's footsteps, dedicating himself and his great energy to humanitarian purposes and the public good.

What could he do? The possibilities are limitless:

He could speak out in defense of human rights, or campaign for better health care in the Third World. He could become a college professor and lecture on arms control, international politics, and environmental issues. He could travel to war zones and mediate cease-fires. He could support programs to make farming in stricken countries more productive. He could write books — and they needn't all be political. He could write about aging, or try his hand at poetry, or even attempt a novel. He could monitor elections in fledgling democracies. He could teach Bible classes. He could work on his relationship with his wife. He could build furniture. Or make wine. Or take up skiing. Or climb Mount Fuji.

Unrealistic? Not the sort of things ex-presidents do? Maybe not most ex-presidents. But Jimmy Carter has done them all.

"Of all the living presidents, he is the only one universally admired for his integrity," says historian Douglas Brinkley, the author of The Unfinished Presidency, a compelling chronicle of Carter's post-White House career. "He is seen as a national treasure — even by people who didn't like him as president."

When Carter's term in office was up, he was 56, just two years older than Clinton is now. He was widely regarded as a failure — a feckless president who blamed American "malaise" for his own inability to deal with soaring inflation and the Ayatollah Khomeini. Today he is renowned for his moral convictions and bedrock honesty. That isn't how the world would see him if he had devoted the last two decades to collecting speaking fees. Bill Clinton, take note.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.