MARTY MEEHAN, a lean and hungry Massachusetts congressman, is caught in a painful dilemma. He has to decide which means more to him — his word or his ambition.

When he ran for the House of Representatives in 1992, Meehan made an ironclad promise to serve no more than four terms. "We should use the liberation of term limits to smash open our gridlocked yet out-of-control Congress," he said. It was a quite a pledge, particularly for a Massachusetts Democrat, and it helped propel Meehan to a dramatic primary victory over the four-term incumbent, Chester Atkins.

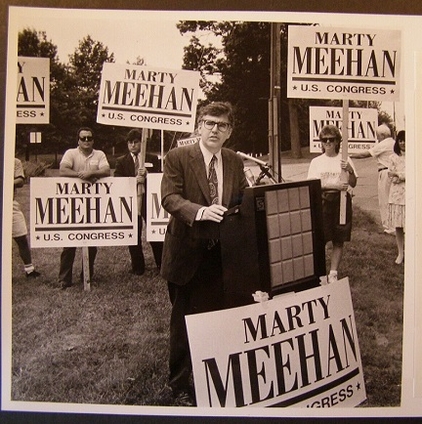

As a candidate for Congress, Massachusetts Democrat Marty Meehan solemnly pledged to seek no more than four terms. |

Now Meehan is a four-term incumbent himself, and he doesn't want to leave. He likes being a congressman. He especially likes the fame he came to know in 1998, when he was involved (albeit on the losing side) in three of the biggest stories on Capitol Hill: the campaign finance bill, the tobacco settlement, and the impeachment of President Clinton.

Meehan can't bear the thought of leaving Congress now, just as the juicy plums of incumbency are dropping into his lap. But he also can't bear to be thought untrustworthy, one more hack whose promises are worthless. So what does he do? Keep his word and walk away from the House? Or renege and become one of those slippery careerists he used to denounce?

Renege, of course.

In recent weeks, Meehan has launched a public relations campaign to give himself cover to break his vow. He's been making the rounds, telling one and all — especially the newspapers — how valuable he has become to his constituents. "I am obviously more effective today that I was when I arrived," he says. "My district would be better off with a member of Congress who utilizes his or her seniority to the advantage of the district."

That's the tired argument every incumbent makes. But the papers seem to be buying it. Meehan has harvested a bouquet of sympathetic columns and editorials, most agreeing with his claim that he is too valuable to replace. Several have assured him that since term limits are a stupid idea, he is not bound by his pledge. He has even been told that going back on a promise can actually be a sign of "growth" and "independence."

Meehan isn't alone. At least three other members of Congress, all Republicans, are poised to abandon their commitment to term limits.

Florida Representative Tillie Fowler advocated term limits when she ran for office in 1992. Her first bill in Congress was a measure restricting House members to eight years in office and senators to 12. As recently as last April, Fowler was adamant on the point. 1998 would be her last congressional campaign, she told reporters. Friends who urged her not to rule out another run were wasting their breath. "I gave my word," she reminded them sharply. Now, with the '98 election safely won, she suddenly has "a more open mind" on the subject.

Scott McInnis of Colorado also took the eight-year pledge in 1992. Of the 50 states, Colorado may be the most steadfastly pro-term limits — it began the limits avalanche in 1990 with the first state law limiting congressional tenure. (The Supreme Court ultimately invalidated all such laws, ruling that only a constitutional amendment can impose term limits on Congress.) Yet McInnis now says his signed promise to leave after eight years was "goofy." He never realized, he claims, just how important seniority is.

The worst betrayal of all, perhaps, is that of Washington's George Nethercutt. His 1994 upset of Tom Foley, the powerful speaker of the House, was driven by the issue of term limits. Foley had angered voters by suing to overturn the state's term-limits law; Nethercutt, by contrast, swore he would serve only three terms and never become a creature of Capitol Hill. But he, too, is planning a double-cross.

"I meant it when I said six years is enough," he told The New York Times, but now he believes that six years "is probably not enough."

Who can wonder at the cynicism of voters, or the contempt they express for politicians? Of all the promises candidates make, none is easier to keep than a promise to leave office after a fixed number of years. The only condition necessary for its fulfillment is the promiser's honesty. Unfortunately, when Potomac — or statehouse — fever breaks out, honesty is usually the first casualty.

As he travels the editorial-board circuit, urging reporters and editors to bless his forthcoming act of bad faith, Meehan has taken to rewriting history. "It was a mistake," he told the Boston Herald, "to blurt out" a term-limits pledge during a debate in 1992. He told editors at the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune that his eight-is-enough vow was a slip of the tongue — "a youthful indiscretion."

It was nothing of the sort. Meehan's term-limits promise was deliberate, calculated, and unconditional. He repeated it often. It was central to his campaign. "I favor limiting members of Congress to four terms," one of his position papers said, "and I commit to serve no longer than that even if term-limit legislation is not enacted."

Up to now, Meehan has been an emblem of how effective and efficient an elected official can be when he knows the term-limits clock is ticking. If he breaks his solemn word, he will become something much less admirable and much, much more common: another lying politician.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.