The prayer that changed the Battle of the Bulge

As belief in God and membership in a house of worship have declined in the United States, so has regular prayer. Fifteen years ago, 58 percent of Americans said they prayed every day, according to the Pew Research Center; now only 45 percent do. (Another 22 percent pray weekly or monthly.) Conversely, 32 percent of US adults — one in three — say they turn to prayer "seldom" or "never," up considerably from the 18 percent who said so in 2007.

Nevertheless, prayer has been a key element in American culture, as befits a society that was born out of a quest for religious autonomy. The "free exercise" of religion is enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Since colonial times, every session of Congress has opened with a prayer. Many of the greatest heroes of American history, from Abraham Lincoln to Martin Luther King, prayed regularly for guidance and success. In his "Four Freedoms" speech, delivered as Europe lay under Nazi domination and vast swaths of Asia were being conquered by Japan, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared that the "freedom of every person to worship God in his own way" was one of the essential conditions for a liberated and peaceful world. Prayers are at the core of some of our most iconic and hopeful songs, including "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," "America the Beautiful," and "God Bless America."

It is probably not true that there are no atheists in foxholes, but prayer in wartime is apt to be prayer at its most fervent. In a nationwide radio address on D-Day, as the massive Allied invasion to liberate Europe was underway, FDR led the nation in prayer.

"Almighty God, our sons, pride of our nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity," he began. "Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith."

But even more memorable than FDR's wartime prayer was the one ordered by Gen. George S. Patton Jr. 78 years ago this week. For weeks, Patton's Third Army had been stymied by the bad weather which kept the Allies' bombers grounded and made it impossible to break the siege of Bastogne and break through the German lines. An increasingly frustrated Patton told Gen. Omar Bradley that the Germans weren't the only or the worst enemy the Allies were facing: The weather was proving an even more serious foe.

On Dec. 8, 1944, the chief chaplain of the Third Army, the Reverend James Hugh O'Neill, got a call from the army headquarters. When he picked up the phone, he heard his commanding officer.

"This is General Patton. Do you have a good prayer for weather? We must do something about these rains if we are to win the war."

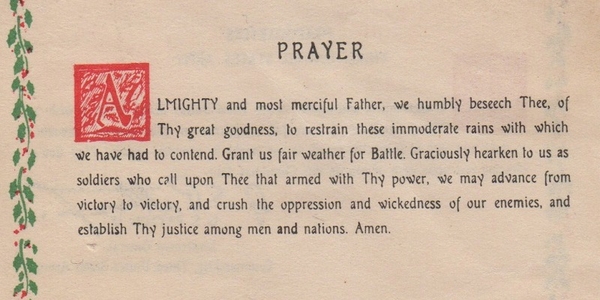

Pocket-sized cards bearing a prayer for an end to "immoderate rains" were distributed to every member of the US Third Army in December 1944. |

O'Neill said he would report within the hour. When a search through his prayer books didn't turn up an appropriate supplication, he set about composing one. On a 3" x 5" index card, he typed out these words:

Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for battle. Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory, and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies, and establish Thy justice among men and nations.

O'Neill took the card to Patton's barracks and handed it to the general, who read it and handed it back — with an astonishing order: "Have 250,000 copies printed and see to it that every man in the Third Army gets one."

But Patton wasn't finished.

"Chaplain, sit down for a moment," he said. "I want to talk to you about this business of prayer."

Patton expressed the view that military success depended on three inputs: a carefully planned strategy, the valor of well-trained troops, and what he called the "unknown" factor. Some people call that factor luck, said Patton, but "I call it God. God has His part, or margin, in everything. That's where prayer comes in." He ordered O'Neill to prepare a communication on the importance of prayer to the nearly 500 chaplains serving in the Third Army, as well as the more than 2,500 organizational commanders of every rank, "down to and including the regimental level."

The communication O'Neill prepared, which bore the bland title "Training Letter No. 5," is a remarkable document. He began by reviewing the successes the Third Army had achieved, observing that to date it had suffered no defeats or forced retreats.

"But we are not stopping at the Siefried Line," O'Neill continued.

Tough days may be ahead of us before we eat our rations in the Chancellery of the Deutsches Reich.

As chaplains it is our business to pray. We preach its importance. We urge its practice. But the time is now to intensify our faith in prayer, not alone with ourselves, but with every believing man — Protestant, Catholic, Jew, or Christian — in the ranks of the Third United States Army. . . .

Urge all of your men to pray, not alone in church, but everywhere. Pray when driving. Pray when fighting. Pray alone. Pray with others. Pray by night and pray by day. Pray for the cessation of immoderate rains, for good weather for battle. Pray for the defeat of our wicked enemy whose banner is injustice and whose good is oppression. Pray for victory, pray for our Army, and pray for peace.

O'Neill arranged for 3,200 copies of his letter to be circulated among the chaplains and organizational commanders. Meanwhile, the 664th Engineer Topographical Company was working around the clock to produce a quarter of a million pocket cards with the weather prayer on one side and a signed Christmas message from Patton on the reverse. The distribution of the cards was organized by the Third Army's adjutant general, Col. Robert S. Cummings. Most of them had reached the troops by Dec. 14.

Two days later, the Battle of the Bulge began. In a surprise attack on the morning of Dec. 16, the Germans — aided by the heavy weather that kept the American planes on the ground — attacked a weakly defended segment of the Allied line on the Luxembourg frontier. "For three days it looked to the jubilant Nazis as if their desperate gamble would succeed," O'Neill recalled. "They had achieved compete surprise. Their Sixth Panzer Army . . . seared through the Ardennes like a hot knife through butter." To the north, meanwhile, the Nazis' Fifth Panzer Army was advancing westward, with the ultimate goal of capturing Brussels. "Had the bad weather continued, there is no telling how far the Germans might have advanced."

But in the chaplain's words, "the prayer was answered." His account continues:

On Dec. 20, to the consternation of the Germans and the delight of the American forecasters who were equally surprised at the turnabout, the rains and the fogs ceased. For the better part of a week came bright clear skies and perfect flying weather. Our planes came over by [the] thousands. They knocked out hundreds of tanks, killed thousands of enemy troops in the Bastogne salient, and harried the enemy as he valiantly tried to bring up reinforcements. The 101st Airborne, with the 4th, 9th, and 10th Armored Divisions, which saved Bastogne, and other divisions which assisted so valiantly in driving the Germans home, will testify to the great support rendered by our air forces. General Patton prayed for fair weather for battle. He got it.

Patton's high regard for prayer seems light years removed from our era, when faith is dwindling almost palpably and people who consider themselves sophisticates increasingly treat religion and prayer as lame superstitions that bitter hicks cling to out of bigotry or ignorance. Yet as the story of the weather prayer makes clear, it was not all that long ago that 250,000 American troops could be supplied with the text of a prayer on the assumption that many of them — perhaps most of them — would turn to God for help.

Of course there is no way to prove that the skies over the Ardennes cleared because tens of thousands of American troops were praying for good flying weather. But the importance of prayer in wartime — particularly in wars fought to "crush the oppression and wickedness" of an enemy like Nazi Germany — used to be taken for granted.

"Fervently do we pray that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away," said Lincoln in his achingly beautiful Second Inaugural Address. All wars cause suffering and destruction; all decent people yearn for the terrible cruelty of war — every war — to end. It is hardly outlandish to wonder whether there is something ethically dubious about treating prayer as a force multiplier, seeking God's assistance in wreaking devastation on an enemy. In the 1970 movie "Patton," with George C. Scott playing the legendary general, a brief scene is devoted to the weather prayer. In Hollywood's fictionalized depiction, the chaplain responds skeptically to Patton's demand. "I don't know how this is going to be received, general," he says. "Praying for good weather so we can kill our fellow man?"

Yet when the only way to end a just war is to win it — as it had to be for Washington in the American Revolution, for Lincoln in the Civil War, and for Allies in World War II — then there is no contradiction in asking for divine help to do so. Even as Lincoln, taking the oath of office for the second time, prayed that the war might "speedily pass away," he also prayed for success: "With firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right," he declared, "let us strive on to finish the work we are in."

The role of prayer in our nation's culture may have diminished in recent decades. But the role of prayer in our history is profound. Many of America's most cosmopolitan and educated leaders have shared the conviction that this is indeed a nation "under God," whose help should be sought through prayer.

Reflecting in Federalist No. 37 on the remarkable unanimity achieved by the Constitutional Convention, James Madison said it was "impossible . . . not to perceive in it a finger of the Almighty hand which has been so frequently and signally extended to our relief in the critical stages of the revolution." At that convention, even the shrewd, inquisitive, worldly, and science-minded Benjamin Franklin argued that appealing to Heaven was essential to success. "I have lived a long time," he told his fellow delegates. "And the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth: that God governs in the affairs of men."

Patton and his men would not have disagreed. In this season 78 years ago, at a crucial juncture of the bloodiest war in history, the Third Army prayed that God might send "fair weather for battle." The fair weather came. The battle was won. The Allies advanced. And five months later, Nazi Germany surrendered. Thank God.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

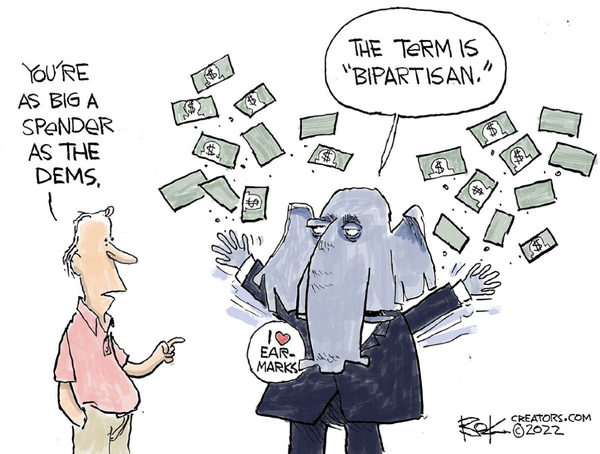

The GOP says yes to earmarks

It is one of the most reliable, and depressing, patterns in national politics. When Republicans are in the minority, they fulminate against reckless government spending, only to outdo Democrats in profligacy after they return to power.

On George W. Bush's watch, for example, federal spending exploded to nearly twice what it had been under Bill Clinton. In 2009 and 2010, to take another example, Tea Party rallies were driven by grassroots outrage at Washington's fiscal recklessness under Barack Obama and a Democratic Congress. But once Republicans were back in the driver's seat, with Donald Trump in the White House and GOP majorities in both houses of Congress, their extravagance made a mockery of everything Republicans had said about the need for fiscal discipline. And that was before the pandemic.

However, there was one notable exception to the Republican habit of talking the talk of fiscal sobriety but not walking the walk: the party's stance against earmarking.

Earmarks — a.k.a. pork barrel spending — are provisions in legislation that direct funds to specific local recipients, bypassing the normal criteria for allocating funds. In the Clinton and Bush years, earmarks exploded, from fewer than 1,000 in 1996 to nearly 14,000 in 2005, according to Brian Riedl, a fiscal policy scholar at the Manhattan Institute. Corruption and scandals related to earmarks exploded, too. Eventually the GOP turned against earmarking. After the 2010 midterm elections, when Republicans gained a sizable majority in the House, they adopted a strict ban against earmarking. In his State of the Union address early in 2011, Obama got on board and vowed to veto any bill containing earmarks: "The American people deserve to know," he said, "that special interests aren't larding up legislation with pet projects."

That ban on earmarks 11 years ago was a rare and genuine fiscal reform. But it broke down last year, when the 117th Congress was sworn in last year under all-Democratic control. Pork barrel line items returned to the federal budget — and many Republicans were happy to resume bellying up to the trough. Just how many became clear last Wednesday, when the House GOP caucus voted against a proposal to restore the ban on earmarks when Republicans return to majority status in their chamber next month.

The proposal was made by Representative Tom McClintock of California, who urged his fellow Republicans to "make a dramatic, concrete, and credible statement that business as usual as Washington is over" by once again pulling the plug on "the wasteful and corrupting practice of congressional earmarking."

But when the caucus voted, only 52 Republicans voted for McClintock's proposed rule, while 158 were opposed. Kevin McCarthy, who hopes to become the next House Speaker, made no effort to block the Republican rush back to earmarking.

As a percentage of all federal outlays, the cost of earmarks may seem trifling: They account for less than $10 billion of the more than $6 trillion (!) Washington will spend this year. But earmarks make it easier to pass the massive spending bills that are crippling the nation with debt. Bloated measures garner more support when wavering members can be won over with line items custom-tailored for their state or district. That was why the late Senator Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, a principled fiscal conservative, used to call earmarks "the gateway drug to corruption and overspending." For one brief shining moment, Republicans could be counted on to say no to that particular variety of Washington intoxicant. It didn't last.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "In Arabic, not a word of peace," Dec. 9, 1997:

The PLO's failure to abide by the terms of the Oslo peace accords has been comprehensive. It has not repealed its noxious covenant. It has not outlawed terror groups. It has refused either to extradite terrorists to Israel or to punish them itself. It has sanctioned the murder of Arabs who sell land to Jews. "Land for peace" has proved a hoax: Israel surrendered the land — all of Gaza and every major town on the West Bank, including Hebron — but the Palestinians never came through with the peace.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"I do wish I could chat longer, but I'm having an old friend for dinner."— Dr. Hannibal Lecter (played by Anthony Hopkins) in "The Silence of the Lambs" (1991)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.