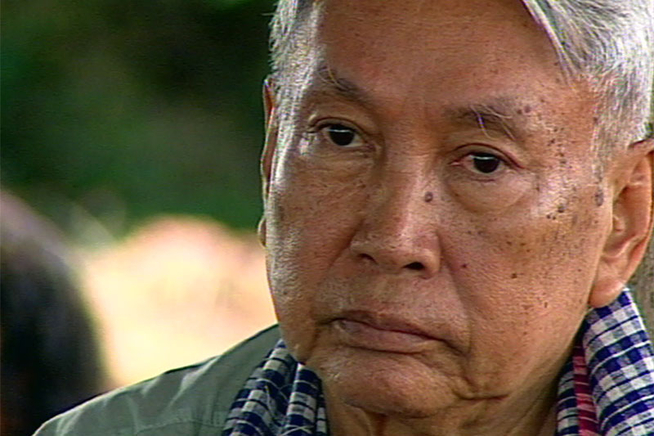

Under Pol Pot's direction, as many as 2 million Cambodians were murdered. He has no regrets. |

IT WILL GO DOWN as the greatest rationalization of the late 20th century. What could top it? "I came to carry out the struggle, not to kill people," says Pol Pot, who supervised the murder of as many as 2 million Cambodians in the 1970s. "Even now, you can look at me: Am I a savage person? My conscience is clear."

In an interview with the Far Eastern Economic Review, Pol Pot admits having ordered many people's deaths, but argues that he had a good reason. "Naturally," he tells journalist Nate Thayer, "we had to defend ourselves." He insists that the mass starvation that swept Cambodia after the Communist takeover in 1975 was caused by Vietnamese agents and claims that the rivers of blood shed by his Khmer Rouge were necessary because the Vietnamese "wanted to assassinate me so they could easily swallow up Cambodia." (The interview is summarized in a Los Angeles Times story that appeared Oct. 23.)

If Pol Pot is capable of having a clear conscience, and there is no evidence that he is lying, anyone is. He may be the greatest mass killer alive today, but like everyone else, he can justify his behavior. He had his reasons. His clear conscience is the ultimate refutation of the belief that human beings can reason their way to goodness. Logic alone does not dictate that murder (or anything else) is bad. In the absence of God, religion, and the Sixth Commandment, it is just as reasonable to conclude that murder is good. Why shouldn't Pol Pot's conscience be clear? As far as he's concerned, the killing fields served a noble purpose.

In a value system shaped only by logic, people who are sure they mean well can decide that the mass murder of 2 million Cambodians is acceptable. Rationality by itself cannot make people ethical. (It is no coincidence that "rationalize" is our word for justifying the unethical.) Without a universal moral code — which means without a God and a religion that emphasize kind and decent behavior — anything goes.

This is not to say that religious people are all moral or that moral people are all religious. It is to say, as the ethicist and author Dennis Prager has formulated it, that "if there is no God, there is no good and evil — there are only opinions about good and evil." We may think that slaughtering Cambodians in order to bring about a radical agrarian Marxist state is bad; Pol Pot thought it was good. Who's to say we're right?

Saloth Sar, to use Pol Pot's given name, was not some ignorant savage who wandered out of the jungle one day to embark on an orgy of bloodlust. He was a trained schoolteacher, "a joyful, pleasant boy who loved life," according to one of his early companions. Educated in France, he taught history and geography and memorized French poetry. Even now, he is described by those who know him as fond of gardening and affectionate with his daughter.

While studying in Paris, he was drawn to communism, one of the two militant antireligious ideologies of the 20th century. The other was Nazism. Both promised utopias — one, a worker's paradise; the other, racial triumph. Both declared war on the moral tradition that began at Sinai. Both demanded absolute loyalty to secular authority — the party, the Fuhrer. And both led to extermination of human beings on a scale never before known.

But if you don't believe in a God who demands that human life be treated with reverence, what's wrong with slaughtering men, women, and children indiscriminately? If "Thou shalt not murder" is just a suggestion, not a moral absolute, who can condemn Pol Pot? "The Nuremberg Trials," says Prager, "were predicated on the belief that there is a universal law. But where does universal law come from? The universe? Neptune?"

At the Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh, at least 14,000 captives of Pol Pot's communists were tortured into confessing imaginary crimes against Angkar, the Khmer Rouge organization. When they confessed, they were killed. Vann Nath, one of only seven inmates to escape Tuol Sleng, has given an account of what happened there.

"The interrogator told me to confess, or else he'd hurt me. I didn't have any answer. He tied an electric wire firmly around my handcuffs and connected the other end to my trousers with a safety pin. Then he sat down again.

" 'Now do you remember? Who collaborated with you to betray Angkar?' he asked. I couldn't think of anything to say. He connected the wire to the electric power, plugged it in . . . I passed out from the shock."

Pol Pot, who denies that Tuol Sleng existed, says his conscience is untroubled. Believe that he speaks the truth. Awaiting trial 35 years ago, Adolf Eichmann said, "To sum it all up, I must say I regret nothing." Believe that he spoke the truth, too. The human conscience is not a computer hardwired to respond to the ethical teachings of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It can just as readily be programmed to operate on a different set of values: those of "Das Kapital," for instance, or "Mein Kampf" or "If it feels good, do it" or "Greed is good."

This is the lesson of Pol Pot's conscience: No one is more dangerous than an antireligious ideologue. Dostoyevsky summed it up in "The Brothers Karamazov" long ago. "If there is no God, everything is permitted."

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.