Carl Sagan and the freedom to doubt

In astronomy, "Sagan's number" refers to the number of stars in the observable universe. That's a value easier to define than to calculate, but in round numbers, according to a 2010 study by Yale astronomer Pieter van Dokkum, it comes to 300,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, or 300 sextillion. (Depending on the meaning of "observable," that number may now be out of date.)

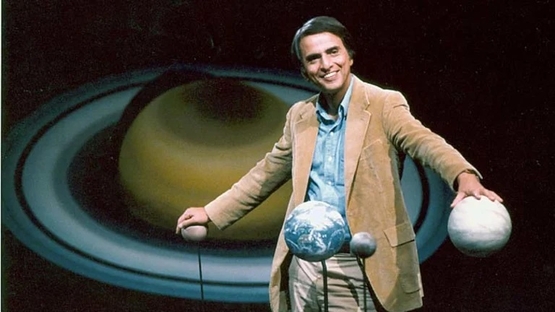

Sagan's number is named for Carl Sagan, the American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, and science communicator who died in 1996. He achieved extraordinary renown in the 1970s and 1980s, especially after PBS broadcast his 13-part television series "Cosmos," which became one of the most widely watched series in the history of American public television. (The dazzling volume of the same title produced as a companion to the series was among the best-selling science books ever published.)

His scientific achievements were considerable. He published more than 600 papers and books in the areas of astrobiology, planetary conditions, the origins of life on earth, the greenhouse effect, and extraterrestrial intelligence. He played a role in numerous NASA planetary space probes and helped write the so-called Arecibo message, an interstellar radio signal incorporating information about humanity that was beamed from earth in the direction of the M13 star cluster in 1974. The honors and awards he received numbered in the dozens; they ranged from the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal to the George Foster Peabody Award for his television work. He was a frequent guest on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and he wrote regularly about science for Parade magazine, a weekly supplement in hundreds of US papers.

As part of his campaign to increase scientific literacy among the general public, Sagan repeatedly emphasized the importance of skepticism and non-dogmatic thinking. He was adamant that extraordinary claims require extraordinary levels of proof and derided pseudoscience and its peddlers. (One of his favorite cartoons, he wrote, showed "a fortune-teller scrutinizing the mark's palm and gravely concluding: 'You are very gullible.'")

Yet while he cast a cold eye on the supernatural claims of religion, he was equally firm that scientists must not fall in love with scientific claims that aren't supported by convincing evidence. "If the ideas don't work, you must throw them away," he wrote in The Demon-Haunted World, the last book he published before his death. "Don't waste neurons on what doesn't work. Devote those neurons to new ideas that better explain the data." He warned against succumbing to confirmation bias — what the pioneering 19th-century English physicist Michael Faraday described as the temptation

to seek for such evidence and appearances as are in the favor of our desires, and to disregard those which oppose them. . . . We receive as friendly that which agrees with [us], we resist with dislike that which opposes us; whereas the very reverse is required by every dictate of common sense.

The lure of confirmation bias is if anything more powerful today, when social media and political polarization relentlessly turn scientific matters into culture-war flashpoints. On issues as different as climate change, gender identity, and COVID-19, too many ideologues on both the right and the left approach public health and science questions through a political lens. News organizations increasingly freeze out or belittle scientific opinions that don't fit an accepted narrative. Leading politicians support or oppose health-care practices on the basis of party politics.

Were Carl Sagan still alive, he would surely be among those pushing back against such blind antiscientific bias. Alas, he was just 62 when he died from complications brought on by a long struggle with bone marrow disease. But in a recently unearthed speech he gave to the Illinois chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union in 1987, Sagan expressed warnings that are even more relevant today than they were at the time. The speech was obtained and transcribed by Harvard scientist Steven Pinker and civil liberties lawyer Harvey Silverglate, both of Cambridge, Mass., who published it this month in the online journal Quillette.

In his address, write Pinker and Silverglate in a brief introduction, Sagan "spoke prophetically of the irrationality that plagued public discourse, the imperative of international cooperation, the dangers posed by advances in technology, and the threats to free speech and democracy in the United States." If those threats raised concerns in 1987, they have grown dire today. Some excerpts from Sagan's remarks:

Science has devised a set of rules of thinking, of analysis, which, although there are exceptions in individual cases (scientists being humans just like everybody else), nevertheless, on average, are responsible for the remarkable progress of science.

And you all know, certainly, what these rules are. Things like arguments from authority have little weight. Like contentions have to be demonstrable. Like experiments must be repeatable. Like vigorous substantive debate is encouraged and is considered the lifeblood of science. Like serious critical thinking and skepticism addressed to new and even old claims is not just permissible, but is encouraged, is desirable, is the lifeblood of science. There is a creative tension between openness to new ideas and rigorous skeptical scrutiny.

These are axiomatic to the scientific method, yet they are flouted routinely, even aggressively. Sagan properly noted that "arguments from authority have little weight" — yet how often are controversial matters now declared immune to dispute because "the science is settled" or "97 percent of scientists agree" or we must "listen to the experts"?

Skepticism, said Carl Sagan, is "the lifeblood of science." |

What is true of science is true of everything, Sagan said. Mistakes are inevitable, which is why it is urgent to allow space for "settled" conclusions to be challenged:

In public affairs, this sort of error-correction machinery in our society is institutionalized in the Constitution. It's institutionalized, first of all, in the separation of powers, and secondly, in the civil liberties, especially in the first 10 amendments to the Constitution: the Bill of Rights.

The founding fathers mistrusted government power, and they had very good reason to, as do we. This is why they tried to institutionalize the separation of powers, the right to think, the right to speak, to be heard, to assemble, to complain to the government about its abuses, to be able to vote or impeach malefactors out of office. . . .

Despite our best efforts, some things we believe are probably wrong. We certainly are very keen on recognizing the errors of past times and other nations. Why should our nation, why should our time, be different? If there are things that we believe, if there are institutions in our society that are in error, imperfectly conceived or executed, these are potential impediments to our survival. How do we find the errors? How do we correct them?

I maintain: with courage, the scientific method, and the Constitution.

At the intersection of science and public policy, nothing is more hazardous than dogmatism enforced through the squelching of dissenting attitudes. A generation before Sagan voiced his warning, an equally renowned scientist, the theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, raised similar alarms. In a 1955 lecture to the National Academy of Sciences, Feynman — who a few years later would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics — addressed what he called "the value of science." He ended with a warning, more desperately needed now than it was then, against closed-mindedness in science and against the urge to demonize those who challenge popular views.

"If we want to solve a problem that we have never solved before, we must leave the door to the unknown ajar," Feynman told his listeners.

In the impetuous youth of humanity, we can make grave errors that can stunt our growth for a long time. This we will do if we say we have the answers now, so young and ignorant as we are. If we suppress all discussion, all criticism, proclaiming "This is the answer, my friends; man is saved!" we will doom humanity for a long time to the chains of authority, confined to the limits of our present imagination. It has been done so many times before.

It is our responsibility as scientists, knowing the great progress which comes from a satisfactory philosophy of ignorance, the great progress which is the fruit of freedom of thought, to proclaim the value of this freedom; to teach how doubt is not to be feared but welcomed and discussed; and to demand this freedom as our duty to all coming generations.

Of all scientific values, Sagan and Feynman both knew, the most invaluable is the freedom to doubt. That freedom is no less indispensable to a healthy civic culture. In a universe of 300 sextillion stars, we will never know everything we don't know. Even here, on the pale blue dot that is the only home humankind has ever known, there are so many unsolved dilemmas, so many questions with only uncertain answers. Those who demand that heterodox thoughts be censored — or self-censored — are playing with fire. For when skeptics aren't safe, all of us are at risk.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Capturing Eichmann

Sixty years after SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann was executed by hanging in an Israeli prison, he can be heard for the first time — in his own voice — boasting of the genocidal crimes he committed during World War II.

A new documentary series — "The Devil's Confession: The Lost Eichmann Tapes" — has been airing in Israel over the past month. At the heart of the series are tape-recorded interviews that Eichmann, a top Nazi organizer, made in Argentina in 1957 with Willem Sassen, a Dutch Nazi sympathizer. At the time of Eichmann's trial in 1961, the prosecution knew of the interviews and had more than 700 pages of transcripts, many with notations in Eichmann's handwriting. But the Israeli Supreme Court excluded the transcripts as evidence, and the prosecution was unable to acquire the recordings themselves. Eventually the tapes ended up in a German government archive. Not until two years ago were Kobi Sitt and Yariv Mozer, the creators of the new documentary, granted permission to use them.

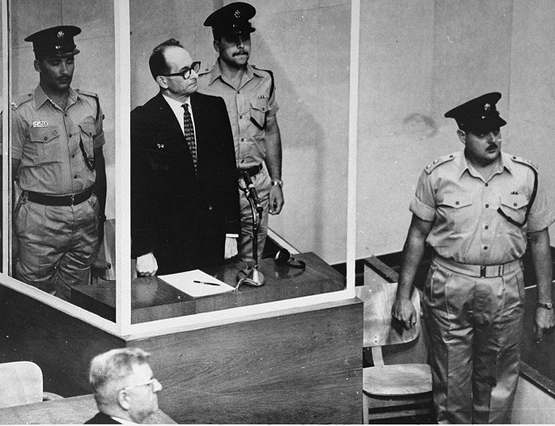

At trial, Eichmann claimed that he was merely a low-level functionary who followed orders and was responsible for nothing. Though the evidence proved otherwise, he denied handling the logistics involved in deporting millions of Austrian, Polish, and Hungarian Jews to ghettos and extermination camps.

On tapes recorded in 1957, Adolf Eichmann is heard boasting of his role in the genocide of Europe's Jews. Above, Eichmann appears before the court in Jerusalem at his trial in 1961. |

"The documentary series intersperses Eichmann's chilling words, in German, defending the Holocaust, with re-enactments of gatherings of Nazi sympathizers in 1957 in Buenos Aires, where the recordings were made," reported Isabel Kershner in The New York Times last week.

Exposing Eichmann's visceral, ideological antisemitism, his zeal for hunting down Jews, and his role in the mechanics of mass murder, the series brings the missing evidence from the trial to a mass audience for the first time.

Eichmann can be heard swatting a fly that was buzzing around the room and describing it as having "a Jewish nature."

He told his interlocutors that he "did not care" whether the Jews he sent to Auschwitz lived or died. Having denied knowledge of their fate in his trial, he said on tape that the order was that "Jews who are fit to work should be sent to work. Jews who are not fit to work must be sent to the Final Solution, period," meaning their physical destruction.

"If we had killed 10.3 million Jews, I would say with satisfaction, 'Good, we destroyed an enemy.' Then we would have fulfilled our mission," he said, referring to all the Jews of Europe.

I haven't seen the new series, though I will be interested to do so when it is made available in the United States. But news of the Eichmann recordings got me thinking about the international reaction in May 1960 when Israeli agents captured the escaped high-ranking Nazi in Buenos Aires and flew him to Israel to face a court of law.

Today, Eichmann's trial and the operation that brought him to the dock are regarded as milestones in the cause of justice and accountability for the victims of genocide.

In the words of one expert — the head of the US Justice Department's Office of Special Investigations — it was "an enormously positive landmark in the history of human rights enforcement" and "was probably more responsible than was any other event for the revival of prosecutorial interest in the Nazi cases in Germany, the United States, and in the lamentably few other countries that pursued a measure of justice in those cases after the 1950s." Eichmann's trial encouraged Holocaust survivors to speak openly for the first time about their experiences and it sparked the development of Holocaust studies as a serious academic discipline. It also launched the process of treating Holocaust remembrance — something rarely thought about in the first decade and a half after the war — as a crucial moral exercise. Above all, it focused global attention on the question of justice for what Nazi Germany had done to Europe's Jews.

So it is startling to realize just how infuriated elite opinion was when a team of Mossad operatives tracked Eichmann down in Argentina and spirited him to Israel.

"Condemnations poured in from around the globe," wrote Daniel Gordis in his award-winning history of the state of Israel.

Argentinean officials, who unabashedly gave Nazis refuge, claimed that Israel's action was "typical of the methods used by a regime completely and universally condemned." The United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 138, stating that Israel had violated Argentina's sovereignty and warned that future similar actions could undermine international peace. The United States, France, Britain, and the Soviet Union all joined in condemning Israel. Argentinean civilians, following the lead of their government's reaction, responded with violent antisemitic attacks on the Argentine Jewish community.

In her 2011 account of the Eichmann trial, the American historian Deborah Lipstadt noted that while countless citizens were as electrified by the Mossad's exploit as if Hitler himself had been found, much of the media erupted in unbridled hostility. "In the space of a month," she wrote, "The Washington Post ran two vituperative editorials condemning Israel's 'jungle law' and predicting that an Israeli trial would be 'tainted with lawlessness,' 'wreak vengeance,' and 'debase the law.'" Continued Lipstadt:

Time condemned Israel's "highhanded disregard of international law." The New York Post predicted that this would be a "show trial" which should rightfully be held in Germany. The Christian Science Monitor, taking an even more extreme stance, argued that Israel's claim to have the authority to adjudicate crimes against Jews committed outside of Israel was identical to the Nazis' claim on "the loyalty of persons of German birth or descent" wherever they lived. Some of the more vituperative attacks came from William Buckley's National Review. He devoted three editorials to the topic within weeks of the capture. In a surprising statement, Buckley described Eichmann as having had "a hand in exterminating hundreds of thousands" (emphasis added). Condemning the proposed trial as a "pernicious" effort designed to speak for a "mythical legal entity (the Jewish People)," Buckley marveled that it was to last three months, whereas the Christian Church's focus "on the crucifixion of Jesus Christ [lasts] for only one week of the year." This, he declared, was symptomatic of the Jewish "refusal to forgive."

There was much, much more of this, as Lipstadt recorded, but here and there other voices expressed other views. A notable exception to the flood of condemnation came from the prominent Argentinian writer Ernesto Sabato, wh0 asked, in the Buenos Aires newspaper El Mundo: "How can we not admire a group of brave men who . . . had the honesty to deliver him up for trial by judicial tribunals instead of . . . finishing him off on the spot?"

In the end, justice was done. Eichmann's trial was fair. His judges were scrupulous. The legitimacy of his prosecution — albeit by the government of a country that did not exist when he committed his enormities — was conducted, as the famed English historian Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote in the London Sunday Times, "unmistakably on the established theory and practice of civilized states."

The anti-Israel hostility and hysteria that erupted when Eichmann was nabbed in Argentina is largely forgotten now. It was of a piece with the anti-Israel hostility and hysteria that erupts routinely whenever the Jewish state acts in defense of its people or its core interests and like most such eruptions, ultimately proved irrelevant. What endured of the episode, as the new documentary underscores, was its heroic embodiment of historical justice, and the establishment of a key principle: that persons who commit crimes against humanity can be called to account for their actions in any place, at any time, and by any nation entitled to try them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

It's July 11. You know what that means.

OK, things in America aren't exactly perfect these days. But some good things endure, like the fact that today is 7-Eleven Day, which means you've got all day to get a free Slurpee — or 12,689 free Slurpees, if you can figure out a way to visit every 7-Eleven from sea to shining sea.

Slurp away! |

Like many other success stories, Slurpees grew from a mistake. They were inadvertently invented in 1958 by Omar Knedlik, the owner of a Dairy Queen in Coffeyville, Kansas. His store lacked a soda fountain, "so he began placing shipments of bottled soda in his freezer to keep them cool," according to Gizmodo. "On one occasion, he left the sodas in a little too long, and had to apologetically serve them to his customers half-frozen."

As it turned out, no apology was necessary: Customers loved the slushy beverages. Knedlik realized he had stumbled on a good idea and set about to develop it.

Five years of trial and error ensued, resulting in a contraption that utilized an automobile air conditioning unit to replicate a slushy consistency. The machine featured a separate spout for each flavor (only two at this point), and a "tumbler" which constantly rotated the contents to keep them from becoming a frozen block.

Knedlik initially thought about calling his new product "Scoldasice" but was persuaded by a local artist, Ruth Taylor, to name it "ICEE." For a rental fee, stores could install ICEE dispensers and enjoy exclusive distribution rights in their territories. "By the mid-1960s, 300 companies had ICEE machines in operation," Gizmodo notes. One of them was 7-Eleven, a Texas-based convenience store. Before long, 7-Eleven had negotiated a licensing agreement with the ICEE company, under which it would pay royalties for the use of Knedlik's contraption, while marketing the product under a different name. The name 7-Eleven invented was "Slurpee." The rest, as Gizmodo recounts, is history.

Since the Slurpee debuted in 1967, over 7 billion have been sold worldwide — one for every person on the planet. Ranging in price from $1.15 to $3, the beverage is cheap, bountiful, and widely consumed in more than a dozen countries, led by Canada.

Yes, Canada. Particularly Manitoba, whose capital, Winnipeg — one of the coldest cities in North America — is the perennial Slurpee Capital of the World. Well, someplace has to be.

Meanwhile, you've only got the rest of today to get yourself a free Slurpee. According to 7-Eleven, they now come in 12 flavors. I hear the Mango Lemonade pairs perfectly with Arguable.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I Wrote Then

25 years ago on the op-ed page

From "Death of a message," July 15, 1997:

Whatever you think of the product he was created to sell, Joe Camel, like all advertisements and commercial symbols, was a message. He was an exercise of free speech. He was the expression of an opinion — an opinion agreeable to some, disagreeable to others, but widely held and unmistakably real. "Joe Camel" is no less filled with meaning — and no less entitled to a stall in the marketplace of ideas — than "Look for the union label" or "Heather has Two Mommies" or "I want to build a bridge to the 21st century." The fact that it is not in people's best interest to smoke is irrelevant to the question of free speech. It is not in people's best interest — many would argue — to join labor unions, live as lesbians, or vote for Bill Clinton. Should messages promoting those choices be silenced by the government, too?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Last Line

"Don't ever tell anybody anything. If you do, you start missing everybody." — J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.