ONCE, THE Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts was renowned for its independence and integrity. Few courts in America could match the SJC in legal brilliance or scholarly eminence. Presided over by such men as Isaac Parker, Lemuel Shaw, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the SJC for many years cast one of the most imposing shadows in American jurisprudence.

But the SJC has declined with age. Instead of independence and integrity, the state's high court is now known for its pliancy and deference to political insiders. In a Boston Globe interview last January, Chief Justice Herbert Wilkins observed that he doesn't mind nepotism and patronage in the judicial system, since they help judges curry favor with state legislators.

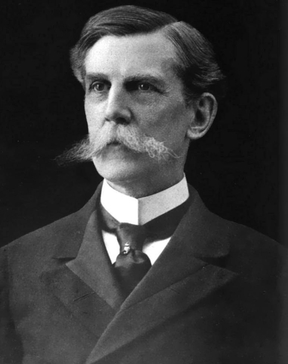

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., one of the brilliant jurists who presided over the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in its heyday. |

"We want to speak kindly to the Legislature," he said, conceding that lawmakers like to stash friends and relatives on the court payroll. "I don't know that people ought to be discriminated against because they happen to be related to a politician." He expressed the hope that he would be judged by his ability to coax the Legislature into authorizing a $685 million courthouse bond bill and a new computer network for the courts.

When the chief justice of the SJC regards the delivery of pork as his highest priority, we are a long way from Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Which brings us to the SJC's 6-0 decision last week to kill the Massachusetts term limits law.

The ruling was a violent insult to Massachusetts voters, who adopted the law by initiative on Election Day 1994. It was also a grave setback for democracy and the rule of law. For in essence, the SJC endorsed the proposition that if the Legislature wishes to stonewall the voters and track mud through the state constitution, no court will interfere.

For six years, Massachusetts politicians have treated term limits proponents with derision and deceit. The proponents, by contrast, have behaved scrupulously. In 1991 they drafted a constitutional amendment limiting legislators and statewide incumbents to eight years in office. After their language was validated by the attorney general, they collected 75,000 signatures to put the measure on the ballot.

But they first had to go to the Legislature, which — under Article 48 of the Massachusetts Constitution — must vote on proposed amendments in a joint session before they can go to the electorate. As long as 25 percent of legislators back an amendment, it is submitted to the voters.

But when the joint session convened on May 13, 1992, the term limits amendment never got a vote. The presiding officer, Bill Bulger, then president of the Senate, arranged to have it sent to the bottom of the agenda. When the joint session convened again on June 10, Bulger refused to bring it up. When it reconvened on June 24, he again refused to allow a vote. And so it went for seven months, through joint session after joint session, until the legislative clock was about to expire.

Stunned by the Legislature's arrogance, term limits advocates turned to the Supreme Judicial Court. In December 1992 they asked the court to order the Legislature to take the required vote. The SJC refused. Under the "separation of powers," it held, it could not compel lawmakers to obey the constitution.

On Jan. 4, 1993, the Legislature met in its final session. No business was transacted. No vote was held. When the time ran out, the amendment was dead.

Angrier than ever, the term limits reformers resolved to start all over — only this time with a statute instead of an amendment. (Proposed statutes can go to the voters without a legislative vote.) What they devised was an initiative that technically would not bar an eight-year incumbent from seeking reelection, but would deny him a spot on the ballot. An incumbent wanting to stay in office would have to run as a write-in candidate — and would get no salary if he won. It was a convoluted path to term limits, but it was the only way to do it without having to amend the constitution.

Once more, the petitions went out. Once more, 75,000 signatures had to be collected. Once more, legislators denounced the initiative in vitriolic terms. (One senator, Stanley Rosenberg of Amherst, compared term limits advocates to Adolf Hitler). But in November 1994 the measure finally appeared on the ballot, becoming law by vote of the people.

There the matter should have ended. But in Massachusetts, it is not the people who have final say. It is the politicians.

One year after the election, a phalanx of legislators asked the high court to declare the new law unconstitutional. To ensure the justices' compliance, the lucrative bond bill so coveted by Chief Justice Wilkins was put on hold. When the court heard oral arguments in the case last May, it signaled loudly and clearly that it was prepared to kill the law. The bond bill was promptly passed.

Last Friday the SJC mowed the statute down. It ruled that politicians' terms can be limited only by amendment. And if lawmakers "defy the requirements of the Constitution" by obstructing an amendment? Too bad, said the justices. Supporters of term limits will just have to live with "discouragement."

When courts refuse to uphold the law, they become worse than useless. The SJC, long fallen from eminence, is now just a tool for political hacks. If Oliver Wendell Holmes could view his successors, he would turn aside in disgust.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.