ECONOMICS AND brilliant wit do not usually go hand in hand, but in a hilarious piece of satire, a French economist has published a devastating rebuttal to all the industries that plead for government protection from competitors' lower prices. If you've ever been seduced by the anticompetitive laments of the steel lobby or the dairy farmers, you owe it to yourself to take a look at this marvelous spoof.

Written in the form of a petition to the French parliament from the candle and lamp industry, it pleads for relief "from the ruinous competition of a foreign rival who apparently works under conditions so far superior to our own for the production of light that he is flooding the domestic market with it at an incredibly low price." As soon as this competitor's product appear on the market, then "our sales cease [and] all the consumers turn to him."

The identity of this ruthless rival? The Sun! Its appearance every morning badly cuts into the demand for the candlemakers' products. Accordingly, they ask the government for assistance:

"We ask you to be so good as to pass a law requiring the closing of all windows, dormers, skylights, inside and outside shutters, curtains . . . and blinds - in short, all openings, holes, chinks, and fissures through which the light of the sun is wont to enter houses." A crazy idea? Not at all, they insist. Making the public spend more money for candles and lamps will mean not only more jobs in the lighting industry but more business for all of its suppliers. Then "we and our numerous suppliers, having become rich, will consume a great deal and spread prosperity into all areas of domestic industry." Force up the price of artificial light and everyone will benefit!

Preposterous? Of course. But the point of this clever parody - a point conveyed more effectively than a 20-page monograph on the folly of protectionism could have done - is that it is no less preposterous when steel companies lobby for stiff duties to stem the "dumping" of inexpensive foreign steel.

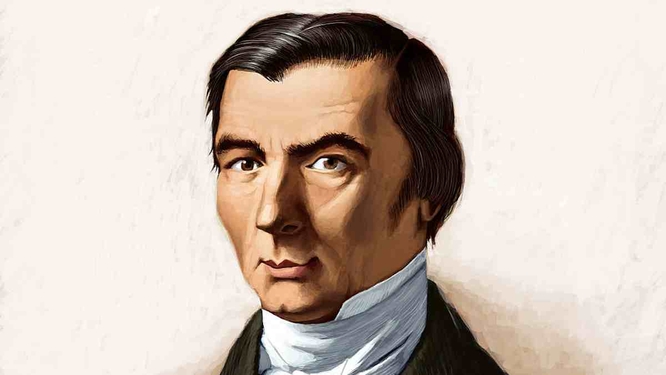

Actually, the author of "The Candlemakers' Petition" didn't really write it with steel in mind: Frederic Bastiat published it in 1845. But it comes as no surprise that a lampoon penned in the 19th century by the man who has been called "perhaps the clearest and most entertaining economist the profession has ever known" loses none of its bite when read in the context of 21st-century trade restrictions.

This year marked the 200th anniversary of Bastiat's birth, and the occasion has not been celebrated with nearly the enthusiasm it deserved. Bastiat was a champion of economic liberty with a nearly unparalleled gift for slaying the sacred cows of government intervention and control. Socialism, collectivism, protectionism, wealth-redist ri bu tion, the "multiplier effect" of state subsidies — Bastiat skewered them all, demonstrating with crystal clarity that society flourishes most when the economy is left to govern itself.

Government's proper role, he wrote, is to secure individuals in their life, liberty, and property — not to interfere with their peaceful interactions or attempt to "guide" the economy. Regulators and politicians cannot improve on the harmony that results from leaving men and women free to trade with each other as they wish. Consider, says Bastiat, the mind-boggling complexity of feeding a great city:

"On coming to Paris for a visit, I said to myself: Here are a million human beings who would all die in a few days if supplies of all sorts did not flow into this great metropolis. It staggers the imagination to try to comprehend the vast multiplicity of objects that must pass through its gates tomorrow, if its inhabitants are to be preserved from the horrors of famine, insurrection, and pillage. And yet all are sleeping peacefully at this moment, without being disturbed . . . by the idea of so frightful a prospect." No central planner could ever hope to accomplish what the undirected free market accomplishes daily.

In his most famous essay, "What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen," Bastiat demolished the fantasy that there are economic benefits to government spending. When the state spends money — to build a convention center, say, or to underwrite mortgages — there are always cheers for the "good" it has accomplished. New jobs! Bigger conventions! More homeowners!

But that is only what you see, Bastiat wrote. What you don't see is what would have happened if the money hadn't gone for taxes. In the private sector, too, it would have created jobs, financed improvements, stimulated the economy. All of that is destroyed when the money is lost to taxes.

Everything the government does, it does at someone's expense. Two hundred years after Bastiat's birth, that simple truth is more relevant than ever. Would that he were still here to teach it.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter