IT WAS a cold diplomatic insult, calculated to sting. Washington's dispute with one of the world's great powers could have been settled amicably, but the secretary of state delivered a slap in the face instead. He wanted to make it unforgettably clear that America's first loyalty is always to those who struggle for freedom — never to the despots whom they struggle against.

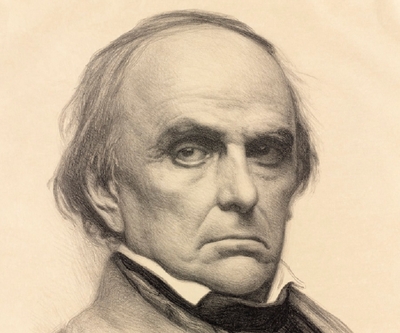

Secretary of State Daniel Webster: "I thought it well to speak out, and tell the people of Europe who and what we are." |

The year was 1850. Daniel Webster, recalled to the State Department by President Fillmore, was nearing the end of a long, illustrious career. At home, Americans were confident of their "manifest destiny" as the world's mightiest democracy. Abroad, they watched with sympathy as a wave of popular uprisings swept across Europe.

Especially stirring to Americans was the revolt of Hungarian patriots under Lajos (Louis) Kossuth, who were fighting for independence from the Austrian Empire. Support for the Hungarian cause and for Kossuth was so fierce that in 1849, President Zachary Taylor dispatched a special envoy, A. Dudley Mann, to meet with Kossuth and even extend US recognition if he thought it advisable.

Kossuth's revolution failed before Mann arrived, but Austria was livid. Chevalier Hulsemann, the Austrian chargé d'affaires in Washington, leveled a protest. He rebuked the United States for its "ignorance" and for showing itself "impatient for the downfall of the Austrian monarchy." The "mendacious rumors" spread by Americans, Hulsemann wrote, were deeply "offensive to the Imperial Cabinet," which resented "all interference in the internal affairs of its government." Either Washington made amends, he warned, or "American policy would be exposed to acts of retaliation."

Austria's hackles would have been easy to smooth. President Taylor, who had authorized Mann's mission, was dead; Webster himself had only just taken over as secretary of state. The Austrian Empire was a military and economic colossus, a vast potential market for US exports. The pragmatic response to Hulsemann's note was obvious: Reassure Austria that Washington had no wish to destabilize the empire and then resume business as usual.

Webster had other ideas. "I thought it well to speak out," he would later write, "and tell the people of Europe who and what we are."

His reply to Hulsemann was blistering. The revolutionary fires burning in Hungary, he informed the Austrian, had been kindled by the American Revolution. Americans cherished the principles of liberty and democracy and did not hesitate to "wish that they may produce the same happy effects throughout his Austrian Majesty's extensive dominions that they have done in the United States." As for Austria's threats, "the government and people of the United States are quite willing to take their chances."

With icy ridicule he cut Austria down to size. "The power of this republic at the present moment," he wrote, "is spread over a region one of the richest and most fertile on the globe, and of an extent in comparison with which the possessions of the house of Hapsburg are but as a patch on the Earth's surface."

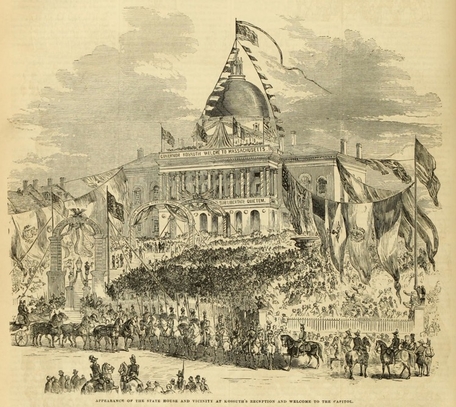

When the Hungarian revolutionary Lajos Kossuth visited Massachusetts in 1852, banners saluting him were draped from the State House and 50,000 admirers massed on Boston Common. |

Across the political spectrum, Webster's words triggered a flood of public praise. American support for democracy in Europe continued unabated. When Kossuth, at Congress's invitation, arrived in the United States the following year, the reaction was explosive.

In New York harbor, warships fired salutes and the Staten Island militia band played "Hail to the Chief." Kossuth embarked on a six-month American tour, setting off tumultuous acclaim almost everywhere he went. In Ohio, 100,000 supporters lined the railroad as he journeyed from Columbus to Cincinnati. Iowa named a county in his honor. The president of the Massachusetts Senate escorted Kossuth from Northampton to Boston, where banners saluting him were draped from the State House and 50,000 admirers massed on Boston Common.

In Washington, Kossuth addressed both houses of Congress and was entertained by the president at a White House dinner. At another banquet, Webster made the toast: "We shall rejoice to see our American model upon the Lower Danube and on the mountains of Hungary. . . . I limit my aspirations for Hungary, for the present, to that single and simple point — Hungarian independence, Hungarian self-government, Hungarian control of Hungarian destinies!"

Austria, more furious than ever, protested again. Hulsemann was recalled to Vienna.

* * *

And today?

Today, the world's leading dictatorship — China — harshly suppresses pro-democracy activists, imprisoning those it hasn't already killed. It prepares to crush Hong Kong's liberties once that tiny colony reverts to Chinese control. It continues to persecute Tibet, reserving special cruelties for Buddhist monks and nuns. To block sovereignty for democratic Taiwan, it stops at nothing — not even missile firings off Taiwan's coast.

And Washington keeps silent. There is no state dinner for the Dalai Lama. No president demands liberty for China's dissidents. No one vows to defend Hong Kong. No Cabinet secretary toasts Taiwanese independence.

Instead there is much talk of trade and money, of most-favored-nation status and "delinking" human rights. Somewhere, ashamed for his country, the ghost of Daniel Webster must weep.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter