UNLIKE SOME of Pope Francis's other headline-generating pronouncements, his description of Turkey's mass murder of 1.5 million Armenians during World War I as "genocide" was anything but inadvertent.

Pope Francis embraces Catholicos Karekin II, the spiritual leader of the Armenian Apostolic Church, during a mass in St. Peter's Basilica marking the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide. |

Speaking at the Vatican during a Sunday mass to mark the centenary of the slaughter, the pope said it is "widely considered the first genocide of the 20th century" — a quote from Pope John Paul II, who used nearly the same words in 2001. But Francis went further, equating the destruction of the Armenians to the Nazi Holocaust and the Soviet bloodbaths under Stalin. And he linked the genocidal Ottoman assault on Armenia, the world's oldest Christian nation, with the epidemic of violence against Christians today, especially by such radical Islamist terror groups as ISIS, Boko Haram, and al-Shabaab.

Turkey reacted angrily, recalling its ambassador to the Vatican and accusing Francis of distorting history and spreading prejudice. On Twitter, the Turkish foreign minister denounced the pope for fueling "hatred and animosity" with his "unfounded allegations." That was no surprise, given the government's vehement history of denialism on the subject. To this day, the use of the word "genocide" to describe the killing of the Armenians is a criminal offense in Turkey, and Turkish diplomats labor mightily to defeat genocide-recognition efforts worldwide.

The journalist Thomas de Waal wrote recently in Foreign Affairs that "no other historical issue causes such anguish in Washington." The political debate over "the G-Word" has consumed countless hours, even as the historical debate — as the pope suggested — has been largely resolved. As de Waal explains, Turkey is so adamant for reasons both material and psychological. Some Turkish politicians fear that acknowledging the Ottoman-perpetrated genocide could trigger claims for financial reparations or territorial concessions. But beyond that is "the emotive power of the word," which was coined in the wake of the Holocaust and is indelibly linked in the public mind with the absolute evil of the Final Solution. "No one willingly admits to committing genocide," writes de Waal, and many Turks seethe at "being invited to compare their grandparents to the Nazis."

Yet Turkish authorities weren't always so reluctant to accurately label the genocidal evil unleashed against the Armenians a century ago.

Talaat Pasha, the powerful Ottoman interior minister during World War I, certainly didn't disguise his objective. "The Government ... has decided to destroy completely all the indicated [Armenians] persons living in Turkey," he brusquely reminded officials in Aleppo in a September 1915 dispatch. "An end must be put to their existence ... and no regard must be paid to either age or sex, or to conscientious scruples."

US Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, flooded with accounts of the torture, death marches, and butchery being inflicted on the Armenians, remonstrated with Talaat to no avail. "It is no use for you to argue," Morgenthau was told. "We have already disposed of three quarters of the Armenians.... The hatred between the Turks and Armenians is now so intense that we have got to finish them. If we don't, they will plan their revenge.... We will not have the Armenians anywhere in Anatolia."

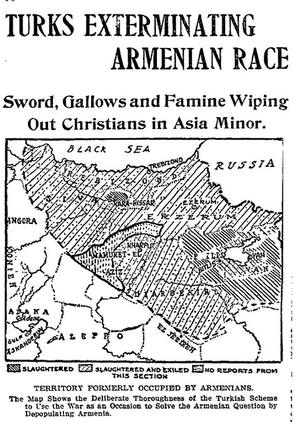

If some of them survived, it wasn't for lack of effort by the killers. Of the roughly 2 million Armenians living in the country in 1914, 90 percent were gone by 1918. The death toll was well over one million; innumerable others fled for their lives. To read eyewitness descriptions of the ghastly cruelties the Armenian Christians were made to suffer a century ago is to be reminded that the jihadist savagery of ISIS and al-Qaeda is not an innovation.

That key fact is one the pope, to his credit, refuses to downplay: Armenians were victims not only of genocide, but also of jihad. In imploring his listeners on Sunday to hear the "muffled and forgotten cry" of endangered Christians who today are "ruthlessly put to death — decapitated, crucified, burned alive — or forced to leave their homeland," Francis was reminding the world that the price of irresolution in the face of determined Islamist violence is as steep as ever.

The jihadists of 1915 murdered "bishops and priests, religious women and men, the elderly, and even defenseless children and the infirm." The world knew what was happening; the grisly details were extensively reported at the time. Just as they are now, and with as little effect.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.