CHRISTMASTIME, 1776, and the cause of American liberty seemed lost.

After a string of defeats in New York, George Washington's troops were in retreat. Fleeing for their lives, they raced across New Jersey, barely keeping ahead of the redcoats. The revolution was going nowhere. Many patriots feared it never would, while Tory collaborators lined up to swear allegiance to the King.

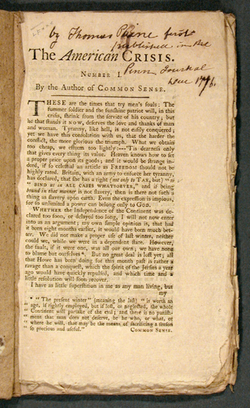

"These are the times that try men's souls," wrote Thomas Paine in 1776. On Christmas Eve, George Washington ordered the demoralized troops of the Continental Army to assemble for a reading of Paine's essay. |

On Dec. 1, Washington's bedraggled army, shrinking daily from disease and desertion, reached Trenton, on the banks of the Delaware River. Gathering every boat they could find so the British would be unable to follow, Washington's men crossed the river into Pennsylvania. There they encamped, safe — but only for the moment. When the river froze, Washington knew, the British would walk across the ice, flatten his army, and roll on to victory in Philadelphia.

He had only 6,000 men — "almost naked," an enemy officer described them, "dying of cold, without blankets, and very ill supplied with provisions." Even worse, enlistments were about to expire. Come Jan. 1, Washington would be left with fewer than 2,000 men. Meanwhile in Trenton, 1,500 Hessians under Col. Johan Rall — German mercenaries who were among the finest fighters in the world — had just taken up quarters.

It seemed hopeless. Morale was crumbling everywhere. "I think," Washington wrote to his brother on Dec. 18, "the game is pretty near up."

But a more fiery American, traveling with Washington's army, refused to despair. Thomas Paine, author of the best-selling pamphlet "Common Sense," published a new essay, the first of a series he called "The American Crisis."

"These are the times that try men's souls," it opened. "The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. . . . Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it!" On Christmas Eve, Washington would order his weary soldiers to muster in groups and listen to their officers read Paine's new essay aloud.

Strangely, the British didn't press their advantage. Rather than close in for the kill, General Howe put up his troops in winter quarters and returned to New York, intending to suspend further fighting until spring.

Washington knew this was his last chance to act. He formed an audacious plan. He would cross the Delaware 9 miles north of Trenton with about 2,400 men — 40 percent of his army — and sneak up on the Hessian garrison. The town had not been fortified, and he hoped to surprise the enemy well before dawn, when they would still be in a boozy slumber after their Christmas festivities.

On Dec. 23, he sent word to Colonel Joseph Reed: "Christmas-day at night . . . is the time fixed upon for our attempt upon Trenton. For Heaven's sake keep this to yourself, as the discovery of it may prove fatal to us."

Indeed, had the British learned of Washington's plan, the revolution would have ended in defeat. His men were exhausted and demoralized, an easy target for the well-fed, well-armed enemy. But Rall, who had once fought for the czar, disdained the patriots as "nothing but a lot of farmers." He refused to prepare for an American attack, so unlikely did he consider one.

If ever fortune favored the brave, it was on that dismal Christmas night in 1776. Rall and his men spent the night carousing, drinking, and playing cards. When a local farmer knocked at his door around midnight with news that the Colonials were coming, a servant refused to let him interrupt the revels. So the farmer scribbled a warning to the Hessian commander — who stuffed it into his pocket, unread.

At 6 p.m. on Christmas Day, the crossing began. With Massachusetts fishermen under Colonel John Glover manning the shallow boats, the patriots made their way across the ice-choked river, through a punishing gale of sleet and snow. For nine hours the Marbleheaders rowed, ferrying boatload after boatload of men and cannon until, at 3 a.m., the last soldier stepped onto the Jersey shore.

Then came the harrowing trek to Trenton, a 9-mile ordeal through freezing wind and hail.

"It will be a terrible night for the soldiers who have no shoes," noted John Fitzgerald, a member of Washington's staff. "Some of them have tied old rags around their feet, others are barefoot, but I have not heard a man complain." As the patriots moved south, bloody footprints stained the snow.

The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, by John Trumbull |

They reached Trenton at dawn and fell upon the Hessians, surprising them utterly. In 45 minutes, it was all over. Of the 1,200 soldiers in the garrison, nearly 1,000 were taken prisoner. Rall, the Hessian commander, was fatally wounded. But the Americans suffered only five casualties, of whom two had frozen to death on the march.

What a rout! Henry Knox, an artillery officer from Boston, wrote to his wife that "the hurry, fright, and confusion of the enemy was not unlike that which will be when the last trump shall sound."

As quickly as possible, Washington's men returned across the river, exhilarated by their triumph. Against all odds, they had struck at the enemy and scored a victory. A week later, recrossing the Delaware to fight the British in Princeton, they would score a second.

The effect on morale — the troops' and the nation's — was tremendous. The Christmas victory at Trenton marked the psychological turning point of the revolution. The pitiful Colonials had taken on the king's forces — if only a single garrison of Hessians — and whipped them. As word of the victory spread like fire, confidence in George Washington and the revolutionary cause revived. America, written off as beaten, would fight on to freedom.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

Discuss Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.

Want to read more Jeff Jacoby? Sign up for "Arguable," his free weekly email newsletter.