THE WORLD'S FOREMOST Holocaust survivor, a man famed for having lifted his voice for the millions who were silenced, cannot talk with his own sisters about the Holocaust.

"I . . . dream about my mother and my little sister," Elie Wiesel writes near the end of And the Sea is Never Full, his new book of memoirs. "I try to learn about their last moments. Hilda walked with them a few steps more than I did. I want to question her about it. I don't dare. We speak every week but only about her health, her son, Sidney, her grandchildren. Yet I would like to know more about her experiences in the camp. . . . I curse the reticence that renders me mute. Neither with Bea nor with Hilda have I spoken of our parents or our home. Am I afraid of bursting into tears?"

Wiesel lived through the Final Solution and he lives with it still; its shadows fall across nearly everything he has done for the past half-century; to remember, to bear witness, has been the constant theme of his life's work. Yet it is the subject he dreads above all others. "I have written books," he says, "but with a few exceptions, they deal with other things . . . . I have written on diverse subjects mostly in order not to evoke the one that, for me, has the greatest meaning."

He has not come close to answering the questions he began asking as a teen-ager. How could it happen? Why was the world indifferent? And God — where was He? Even now he doesn't know what to call the Nazis' genocidal war against the Jews. Sometimes he calls it the Holocaust, sometimes "the Tragedy," "the abyss," "the Events," "the Kingdom of Night." Sometimes, simply — "over there."

"In truth," he writes, "there is no word for the ineffable."

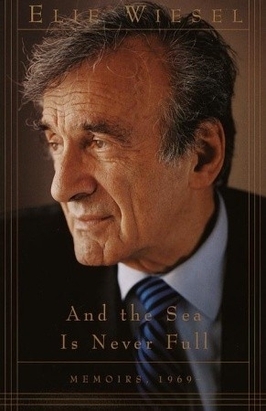

Wiesel is one of the great men of the 20th century; the completion of his memoirs is therefore news. His first volume, All Rivers Run to the Sea, left off in 1969. Wiesel was then 40, the yeshiva student from Sighet, Rumania, who had returned from the death camps, found his voice, and become a writer of international repute. And the Sea is Never Full opens in Jerusalem with his marriage and covers the 30 years since.

By any standard, they have been years of extraordinary accomplishment. Wiesel has made his mark as an author, a teacher, a champion of human rights, a citizen of the world. He has produced 40 books, won millions of admirers, become the confidant of presidents, received the Nobel Prize.

And he has done it all while keeping one foot in Auschwitz.

"In truth," he says, "we have not left the Kingdom of Night. Or rather: It refuses to let us go. It is inside us. The dead are inside us. They observe us, guide us. They wait for us. . . . They are judging us."

The effect Wiesel has on his listeners can be remarkable. In 1985, he testified on the Genocide Convention before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. "When I find out that Jesse Helms is chairing the session, my instinct is to . . . head back to New York, for this Southern senator and I clearly have few ideas in common." He was not encouraged when Helms introduced him. "I realize that he has no idea who I am. He reads a text evidently prepared by his aides: Everything in it sounds false, even my name."

Then the survivor of the extermination camps began to speak. Intently, Helms listened. In the end, the chairman was not swayed by Wiesel's plea that leaving the treaty unratified would amount to a betrayal of the victims. But he paid close attention, and remained "silent for a long moment. He then thanks me in such flattering terms that the entire committee takes notice. Is it the first time he has heard a Jew expressing himself as a Jew? Or is it just a display of southern courtesy? . . . Amazingly, at the conclusion of my testimony, Helms interrupts the session to escort me to the door."

Helms is not the only one who has found Wiesel's voice impossible to ignore.

In 1966, New York's prestigious 92nd Street Y invited the young author to speak. He was to share the program with the novelist Jean Shepherd, but after he spoke, much of the audience left.

Recalls Wiesel: "Never mind, I told myself, while counting the few friends and strangers scattered through [the hall]; so they won't invite me again." He gave it his best shot — read a page from this book, discussed a passage from that one. The audience sat in silence. "God, make this torture come to an end," he silently prayed.

Finally it was over. "Only it wasn't," he writes. In the 34 years since that night, he has returned to lecture at the Y more than 120 times. His annual talks there and at Boston University are typically standing-room-only affairs. Those who hear Elie Wiesel's voice usually return to hear it again.

In Oslo, on the night he receives the Nobel Prize, a torchlight parade is held in his honor. From every corner of Norway, marchers stream to pay him homage. "Since Schweitzer," he overhears a journalist say, "there hasn't been anything like it."

Still, he wonders: Has it all been in vain? He fears that, "like Kafka's unfortunate messenger . . . his message has been neither received nor transmitted. Or worse — it has been, and nothing has changed. It has produced no effect. . . . Everything goes on as though the messenger had forgotten the dead whose message he had carried."

It is a thought to haunt us all.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on X (aka Twitter).

Discuss his columns on Facebook.

Want to read more? Sign up for "Arguable," Jeff Jacoby's free weekly email newsletter.