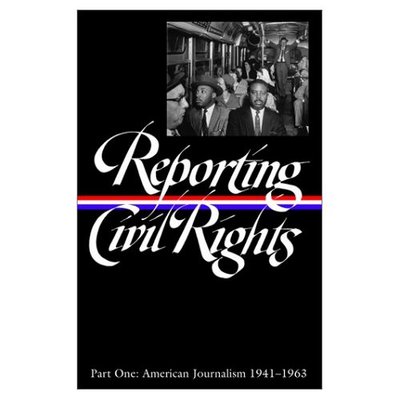

WHEN STROM THURMOND AND LESTER MADDOX died at the end of June, I was making my way through Reporting Civil Rights, the Library of America's new two-volume anthology of American journalism -- newspaper stories, magazine pieces, book excerpts, and other writings -- on what has been called the Second American Revolution: the 20th-century struggle for racial freedom and justice in the United States.

One doesn't have to read up on the civil rights movement to know that the South Thurmond and Maddox departed from last month is utterly changed from the South in which they grew up. But it's one thing to be aware of that transformation as a historical fact. It's something else -- something much more vivid and astonishing -- to experience it through the words of writers who were hurrying to record it and make sense of it as it was happening around them.

The nearly 200 items collected in Reporting Civil Rights were published between 1941 and 1973. I read none of them when they first appeared. I wasn't even born until more than halfway through that 32-year span -- around the time John Howard Griffin was describing, in Black Like Me, what it was like to be a black passenger on a Greyhound bus in Mississippi:

The driver stood up and faced the passengers. "Ten-minute rest stop," he announced. The whites rose and ambled off. Bill and I led the Negroes toward the door. As soon as he saw us, the driver blocked our way. . .

"Where do you think you're going?" he asked. . .

"I'd like to go to the rest room." I smiled and moved to step down.

He . . . shouldered in close to block me. "Does your ticket say for you to get off here?" he asked.

"No sir, but the others --"

"Then you get your ass back in your seat and don't you move till we get to Hattiesburg," he commanded.

"You mean I can't go to the --"

"I mean get your ass back there like I told you," he said, his voice rising.

To be black in the South when Thurmond and Maddox came of age was to be routinely degraded like this, to be reminded at every turn that your honor and dignity counted for nothing, that you could be insulted and abused with impunity. You could be treated that way when all you wanted was to use the bathroom, and you could be treated that way -- as Jack H. Pollack reported in The American Mercury in 1947 -- when all you wanted was to register to vote:

The most frequent trap "question" in Southern literacy tests is to translate -- and spell correctly -- obscure Latin phrases. . . . Registrars reject Negro applicants for not properly answering such . . . questions as "Boy, what's the meaning of 'delicut status quo rendum hutt?'"

If the bewildered applicant ponders the phrase, the registrar continues: "Maybe that's too hard for you. Here's an easy one. If the angle plus the hypotenuse equals the subdivided of the fraction, then how many children did your mother miss having?"

Maddox became famous in 1964 as a segregationist so unyielding that he sold his Atlanta restaurant rather than serve black customers. Two years later, brandishing the pick handle that became his symbol, he rode his fame into the Georgia governor's mansion. Sixteen years earlier, Thurmond had run for president -- and gotten 1.1 million votes -- with the cry that "all the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the Army cannot force the Negro into our homes, our schools, our churches, and our places of recreation and amusement."

Such naked racism is unthinkable today. It would kill, not launch, any politician's career. When Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott praised Thurmond's 1948 campaign in a birthday toast last year, it ended up costing him the leadership.

What is astonishing in all this is not the bigotry toward blacks that Southerners like Thurmond and Maddox and even Lott -- and, for that matter, millions of Northerners -- took in with their mothers' milk. It is the speed and thoroughness with which that kind of bigotry became intolerable to whites. In the space of only a few decades -- a blink of an eye, historically speaking -- America repudiated the racial cruelty and meanness that had always been part of its makeup.

The stories preserved in Reporting Civil Rights seem like snapshots from an alien land. The lynching of 16-year-old Emmett Till for speaking to a white woman, George Wallace's vow to "stand in the schoolhouse door" and block integration at the University of Alabama, the anxiety of Mississippi newspaper editor Hodding Carter over his decision to begin referring to married black women with the courtesy title of "Mrs." -- such scenes, once so typical in this land, are now inconceivable.

Strom Thurmond and Lester Maddox are dead and so is the entrenched racism in which America once was steeped. Intolerance still exists and perfect color-blindness is still a long way off. But to look back at where we were is to see how incredibly far we've advanced. In the ways that mattered most, we did overcome.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).

-- ## --

Follow Jeff Jacoby on Twitter.

"Like" Jeff Jacoby's columns on Facebook.